Nipah virus: Anatomy of an outbreak

The way Kerala has handled the Nipah virus outbreak holds crucial lessons for the rest of India. Priyanka Pulla reports on how a deadly virus is being tackled by an alert administration

At around 2 a.m. on May 17 morning, a grievously sick Mohammed Salih, a 28-year-old architect from Kerala’s Perambra town, was rushed by his family to Kozhikode’s Baby Memorial Hospital. Salih was vomiting, had a high fever, and was in a mentally agitated state. The doctor on call, critical care physician A.S. Anoop Kumar, knew these symptoms meant encephalitis, an inflammation of brain tissue that kills hundreds in India every year. Kumar tried to stabilise Salih, but by around 9 a.m., when the hospital’s neurologists came to examine him, it was obvious that something was very wrong.

Even though Salih was receiving top-end care, his condition was worsening rapidly. He had some very peculiar symptoms, recalls Chellenton Jayakrishnan, one of the neurologists who treated him. His heart was racing at over 180 beats per minute and his blood pressure had shot up. His limbs were limp, displaying no reflexes. These symptoms were unlike any encephalitis cases that the team had ever seen. Jayakrishnan and his colleagues ruled out, one by one, dozens of common causes of encephalitis. Salih couldn’t have Japanese encephalitis. The mosquito-borne infection typically doesn’t affect more than one person in a household, and his younger brother, Sabith, had died about 12 days ago after showing similar symptoms. His father and aunt, too, had contracted the infection.

Rabies, another possible cause of encephalitis, was ruled out too. “If the family had been exposed through a common pet, they would have fallen sick at the same time,” says Jayakrishnan. Salih had fallen sick days after Sabith did. So, was this a case of poisoning? The team ruled this out, too. Toxins could trigger encephalitis-like symptoms but were usually not accompanied by fever.

The neurologists knew by then that they were looking at an exotic virus, possibly never seen in Kerala before. Anoop Kumar decided to call for help. He turned to virologist Govindakarnavar Arunkumar at Karnataka’s Manipal Centre for Virus Research (MCVR), about 300 km from Kozhikode. Salih’s samples were dispatched to MCVR.

Forty-seven-year-old Arunkumar has investigated several mystery outbreaks of encephalitis in the past. In 2015, his team found a recurrent epidemic in Uttar Pradesh’s Gorakhpur to be Scrub Typhus, a diagnosis that was later confirmed by other researchers. A year later, he joined hands with virologist T. Jacob John to uncover the etiology of an encephalitis-like syndrome in Odisha’s Malkangiri district. For four years now, Arunkumar has been heading a surveillance project which tests patients with fever in 10 States for over 40 pathogens. As part of this project, MCVR upgraded one of its labs to Biosafety Level 3 two years ago, so they could work with highly lethal pathogens like the Kyasanur Forest Disease virus. This upgrade gave Arunkumar the chance to expand his testing repertoire. And the pathogen he was eyeing was the deadly Nipah virus.

A serendipitous diagnosis

The Nipah virus made its first documented appearance in Malaysia in 1998. There, the virus is believed to have jumped from fruit bats of the Pteropus species to domestic pigs paddocked under the trees where such bats roost. From the pigs, the virus travelled to pig breeders, infecting and killing about 105 of them in an outbreak. Nipah next appeared in Bangladesh, triggering nearly 15 outbreaks in the 2000s. The pathogen had a different modus operandi in that country. It mainly infected people who had a taste for raw palm sap, which is frequently contaminated by bat urine and saliva. Once the virus spread to humans, it was transmitted from one person to another through respiratory droplets, a feature that wasn’t seen in Malaysia.

Nipah killed nearly 70% of those it infected in Bangladesh, compared to 40% in Malaysia. During the epidemic years in Bangladesh, the virus also crossed the border to enter West Bengal — twice. The outbreaks occurred in 2001 and 2007 in the districts of Siliguri and Nadia, killing 70 people.

Virologist Govindakarnavar Arunkumar, head of the Manipal Centre for Virus Research, with his team at the Kozhikode Medical college.

Arunkumar was interested in testing for Nipah for two reasons. First, among the States covered by his surveillance project were Tripura and Assam, both across the border from Bangladesh and potential geographies for Nipah. Second, the virus is thought to be a probable bioterrorism agent. So, in August 2017, the MCVR team was trained by the United States’ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to test for the Nipah virus. This made the Manipal laboratory only the second facility in India capable of doing so, apart from Pune’s National Institute of Virology (NIV). It was a serendipitous move.

When Arunkumar received Salih’s samples on May 18, he also ruled out common causes of encephalitis such as the Japanese encephalitis virus, the Herpes Simplex virus and Leptospira bacteria. Only one pathogen seemed capable of causing Salih’s symptoms and leading to sickness among several family members at the same time. “It was Nipah,” says Arunkumar.

Meanwhile, doctors at Baby Memorial had also come to the same conclusion. Nipah had crossed Jayakrishnan’s mind on the first day. By the second day, the team had browsed through medical journals and found that Salih’s symptoms closely matched those of the patients affected in the 1998 Malaysian outbreak. Arunkumar ran the samples through a diagnostic test called Real Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR), which detects viral genetic material. Salih, his father V.K. Moosa, and his maternal aunt Mariyam Kandoth all tested positive for Nipah.

As this story went to print, Nipah had claimed the lives of 17 of the 19 people it had infected in Kozhikode, a mortality rate of 89%. The outbreak triggered widespread panic, with families in Perambra deserting their homes en masse. As speculation grew about how the virus was transmitted, N-95 masks appeared all over Kozhikode. When officials announced that the virus could spread through fruits that were half-eaten by bats, people cut down on their fruit purchases.

But without the prompt diagnosis, it could have been worse. In Bangladesh, the first few outbreaks killed dozens in the districts of Meherpur and Naogaon, but were not recognised as Nipah until after they ended. In the 2001 Siliguri outbreak, investigators figured out that it was the Nipah virus that was infecting people only six months later. By then, 60 people had been infected and 45 had died.

India has a poor record of outbreak investigations. About 10,000 people develop encephalitis-like symptoms each year but never get a diagnosis. Some regions, such as Uttar Pradesh’s Gorakhpur and Bihar’s Muzaffarpur, saw thousands of deaths in repeated annual outbreaks before the causes were established. Against this background, the discovery of an exotic pathogen in the very second patient hit by an outbreak, as was the case in Kozhikode, has few precedents.

A brisk State response

Once MCVR had pinpointed the Nipah virus, they had to move quickly. Under the 2005 International Health Regulations, India is obligated to report outbreaks of emerging infectious diseases to the World Health Organisation. The MCVR team had to therefore be doubly sure of its findings. The only way to be so was to ask NIV, Pune, to run Nipah diagnostic tests on a second set of the Perambra family’s samples. As they waited for NIV’s confirmation, Arunkumar told the Baby Memorial doctors that they were dealing with a deadly new virus, and that suspected patients should be isolated immediately. “But we didn’t release the name,” says Arunkumar. Revealing the name publicly would require NIV’s verification, which only came on May 20.

But the State health-care machinery did not wait for confirmation. Within hours of Salih’s arrival at Baby Memorial, Kozhikode’s district medical officer, V. Jayashree, had learnt of it. She put together a team of entomologists and visited Salih’s Perambra home on the morning of May 18. They collected mosquito samples and fogged the area, just in case the mosquitoes were the disease vectors.

By the time Arunkumar shared the final results on May 20, State medical associations and government doctors were already on high alert. The State’s Health Minister, K.K. Shylaja, was in the city to oversee the outbreak response. It was easy to move ahead at this point. On May 20 morning, an officer trained in Ebola outbreak protocols instructed the State’s doctors in infection-control measures — isolating patients, using surgical masks and decontaminating surfaces. It was an extraordinarily swift response by any measure. Yet, according to the State’s Director of Health Services, R.L. Saritha, this was routine procedure. “There were two cases of encephalitis. We wanted to prevent the third. This is the usual response in Kerala to all outbreaks,” she says.

Two waves slip through

For all of the Kerala government’s agility in tackling Nipah, the virus proved to be a formidable adversary. When Salih contracted the infection from his younger brother, so did several others. This was the first wave of infection, and Sabith was patient zero — the first to fall sick.

By all accounts, Sabith was a well liked 26-year-old. A plumber by profession, he loved children and animals, says his cousin Jabir. Today, a colony of rabbits sit in a cage in the family’s abandoned Perambra home. They are fed by the neighbours.

Some time on May 3, Sabith grew feverish. His family took him to the Perambra Taluk Hospital, where his condition worsened quickly. On May 5, when he began to lose consciousness, the family shifted him to the Kozhikode Medical College. Later in the night, Sabith died. But during his stay in Perambra Taluk Hospital and the medical college, nurses attended to him, and dozens of neighbours came to look him up.

Such close contact with patient zero led to seven new cases in Perambra Taluk Hospital and 10 in Kozhikode Medical College. Meanwhile, one of the patients infected in the first wave at Perambra went on to get admitted at the Balussery Taluk Hospital on May 17. He infected yet another person, raising the possibility of a second wave of infection at the Balussery hospital. Nipah spreads mainly through respiratory droplets, and sicker patients secrete more virus. It was only in Baby Memorial, which had stricter infection-control protocols, that transmission seems to have stopped.

Please note that under 66A of the IT Act, sending offensive or menacing messages through electronic communication service and sending false messages to cheat, mislead or deceive people or to cause annoyance to them is punishable. It is obligatory on kemmannu.com to provide the IP address and other details of senders of such comments, to the authority concerned upon request. Hence, sending offensive comments using kemmannu.com will be purely at your own risk, and in no way will Kemmannu.com be held responsible.

Similarly, Kemmannu.com reserves the right to edit / block / delete the messages without notice any content received from readers.

Final Journey Of Theresa D’Souza (79 years) | LIVE From Kemmannu | Udupi |

Invest Smart and Earn Big!

Creating a World of Peaceful Stay!

For the Future Perfect Life that you Deserve! Contact : Rohan Corporation, Mangalore.

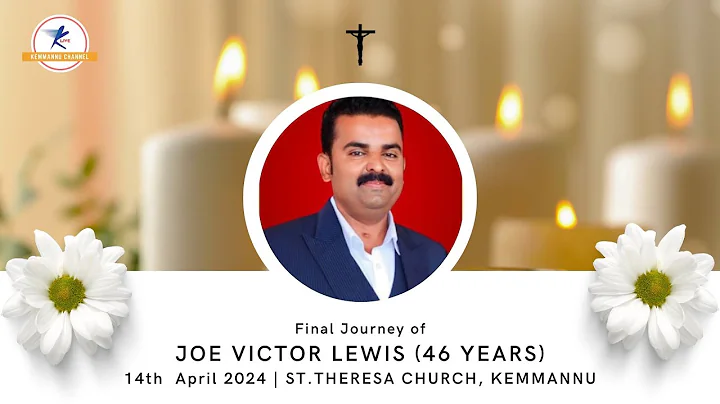

Final Journey Of Joe Victor Lewis (46 years) | LIVE From Kemmannu | Organ Donor | Udupi |

Milagres Cathedral, Kallianpur, Udupi - Parish Bulletin - Feb 2024 Issue

Easter Vigil 2024 | Holy Saturday | St. Theresa’s Church, Kemmannu, Udupi | LIVE

Way Of Cross on Good Friday 2024 | Live From | St. Theresa’s Church, Kemmannu, Udupi | LIVE

Good Friday 2024 | St. Theresa’s Church, Kemmannu | LIVE | Udupi

2 BHK Flat for sale on the 6th floor of Eden Heritage, Santhekatte, Kallianpur, Udupi

Maundy Thursday 2024 | LIVE From St. Theresa’s Church, Kemmannu | Udupi |

Kemmennu for sale 1 BHK 628 sqft, Air Conditioned flat

Symphony98 Releases Soul-Stirring Rendition of Lenten Hymn "Khursa Thain"

Palm Sunday 2024 at St. Theresa’s Church, Kemmannu | LIVE

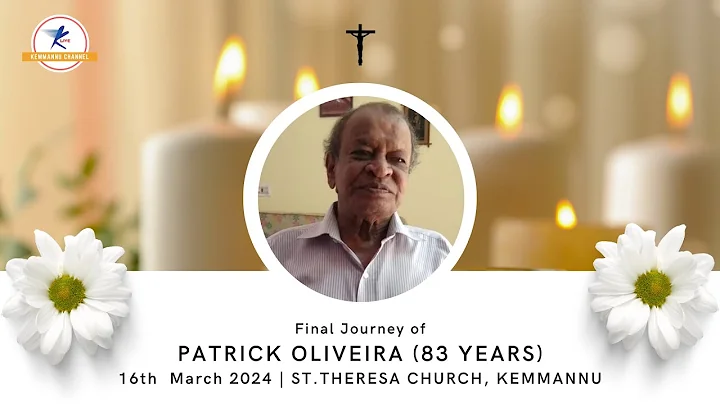

Final Journey of Patrick Oliveira (83 years) || LIVE From Kemmannu

Carmel School Science Exhibition Day || Kmmannu Channel

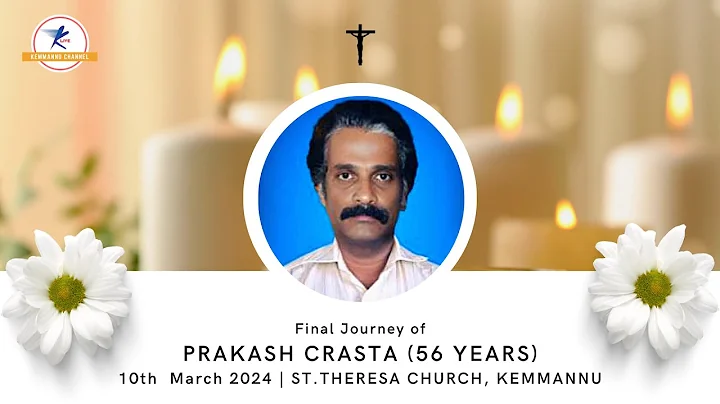

Final Journey of Prakash Crasta | LIVE From Kemmannu || Kemmannu Channel

ಪ್ರಗತಿ ಮಹಿಳಾ ಮಹಾ ಸಂಘ | ಸ್ತ್ರೀಯಾಂಚ್ಯಾ ದಿಸಾಚೊ ಸಂಭ್ರಮ್ 2024 || ಸಾಸ್ತಾನ್ ಘಟಕ್

Valentine’s Day Special❤️||Multi-lingual Covers || Symphony98 From Kemmannu

Rozaricho Gaanch December 2023 issue, Mount Rosary Church Santhekatte Kallianpur, Udupi

An Ernest Appeal From Milagres Cathedral, Kallianpur, Diocese of Udupi

Diocese of Udupi - Uzvd Decennial Special Issue

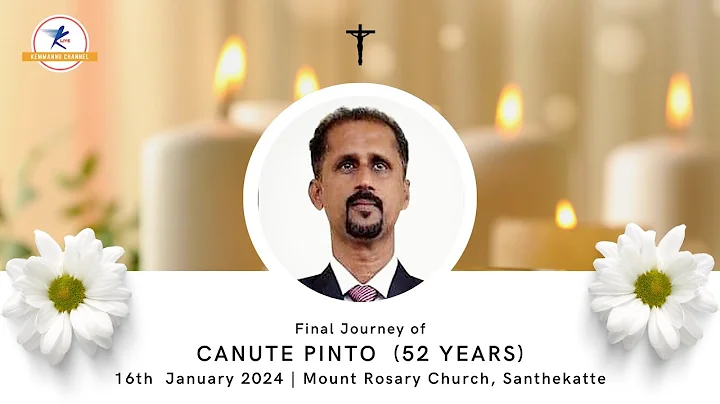

Final Journey Of Canute Pinto (52 years) | LIVE From Mount Rosary Church | Kallianpura | Udupi

Earth Angels Anniversary | Comedy Show 2024 | Live From St. Theresa’s Church | Kemmannu | Udupi

Confraternity Sunday | St. Theresa’s Church, Kemmannu

Kemmannu Cricket Match 2024 | LIVE from Kemmannu

Naturya - Taste of Namma Udupi - Order NOW

New Management takes over Bannur Mutton, Santhekatte, Kallianpur. Visit us and feel the difference.

Focus Studio, Near Hotel Kidiyoor, Udupi

Earth Angels - Kemmannu Since 2023

Kemmannu Channel - Ktv Live Stream - To Book - Contact Here

Click here for Kemmannu Knn Facebook Link

Sponsored Albums

Exclusive

An Open ground ‘Way of the Cross’ observed in St. Theres’s Church, Kammannu. [Live-Streamed]

Udupi Bishop Most Rev. Gerald Issac Lobo Celebrates Palm Sunday at Kemmannu Church

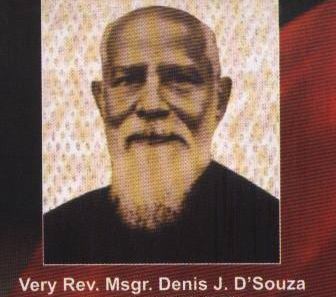

The architect of various Churches, Schools, Hospitals and Colleges….. Msgr Denis Jerome D Souza.

Konknani Writers’ Association Literary Award Conferred on Dr. Gerald Pinto

Celebrating Love Across Languages: A Valentine’s Day Special

Udupi: Kemmannu.com Journo Richard D’Souza Felicitated by Paryaya Sri, Sri Sugunendra Tirtha Swamiji.

Let the unity of senior players be an example to the youth - Gautham Shetty - Alfred Crasto Felicitation - Match Livestream.

Bali, Indonesia: Royal Singaraja Award to Mangalorean NRI Philanthropist Dr. Frank Fernandes. [Video]

MTC - Milagres towards Community – An Outreach program on 14th December, 2023

TODAY -

TODAY -

Write Comment

Write Comment E-Mail To a Friend

E-Mail To a Friend Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter  Print

Print